Teaching into the void - Reflections on ‘blended’ learning and other digital amenities

Teaching into the void - Reflections on ‘blended’ learning and other digital amenities

In this essay Donatella Della Ratta shares her reflections on hybrid learning/teaching and, overall, on our screen life.

Tried to save myself but my self keeps slipping away

Tried to save myself but my self keeps slipping away

Tried to save myself but my self keeps slipping away

Tried to save myself but my self keeps slipping away

Talking to myself all the way to the station

Pictures in my head of the final destination

‘Into the Void’ – Nine Inch Nails

Think of those humans who are attractive for the primary reason of how the presentation of their body is impenetrable or brooding or fierce

or impassive with brooding or fierceness.

This category of desire is simple, slightly mechanistic:

to penetrate the brooding, fierce, impenetrable presentation

– Ann Boyer

Speaking, I’m on display—a pornographic exhibit

– Wayne Koestenbaum

Teaching Into the Void

Reflections on ‘blended’ learning and other digital amenities

By Donatella Della Ratta

Preface

This essay combines the experiences of teachers and students* in the turn to ‘blended learning’ during the Covid-19 pandemic, to build prefatory theories of new, emergent phenomena—from the exhaustion produced by constant ‘self-gazing’ and its role in ‘zoom fatigue’, to the anxieties and oppressions of the dominant interfaces (The Tyranny of the Rectangle) and their consequential resistance techniques (Camera On, Or Camera Off: That is the Question). Through anecdotes and personal accounts, we will enter a founding critique and examination that aims to walk these interactions and isolations with both compassion and criticality, towards a counter-politics reliant on exposure, as well as poesis. A counter-politics that finds and forms itself in the aural rather than the visual (Intimacy Out of the Void), one that is most present (and most potent) in the ‘awkward moments’ of lags, lapses, glitches, bandwidth failures and frozen frames (In Praise of Awkwardness).

The emphasis lies throughout on withstanding naturalization and remaining in defiance of the ‘normalization’ efforts and narratives that pertain to all of the above. There is an urgency here.

This is a direct account, examination, and rebuttle, of what it means to be a teacher and a student during the techno-determinist moment of ‘the Corona Crisis’—a crises of education, embodiment, and alienation, in more ways than one.

* All interviews were conducted with students and teachers of John Cabot University in Rome, unless otherwise noted. Those who wished to do so anonymously, remain unnamed.

—

‘Shall I look over here? Over here, or over here?’, Igor ‘Yes Men’ Vamos asked his clueless and appalled students in a hilarious parody of our Zoom/Teams/Meet daily tragedy. Vamos’s skit has become a sad, accurate reproduction of the everyday experience of both students and teachers, now forced to study under digitalized, remote conditions resultant of the Covid-19 pandemic. This crisis of Corona has produced innumerable crises of and for education. These crises span the troubles of sociality and substitutive interfaces, to the ails of the isolated individual bodies and minds—troubles which arise simply from being a human subjected to these new environments in their various forms of virtuality and isolation.

To begin with the semantics, there is an entry point provided by the introduction of what has come to be known as ‘blended learning’. As a teacher, before being obligated to move to this environment (aka ‘hybrid’) where we would teach both online and on site—which we can see was and is an attempt to achieve ubiquity and maintain the myth of multitasking as noble, wise, and possible—those words, ‘blended learning’, sounded sweet and promising.

Digital capitalism has a talent for name-selection and (re)branding flawed substance with bombastic labels. For me, ‘blended learning’ initially evoked images of British chaps drinking impossible amounts of scotch in crowded pubs, a motif that my domesticated post-pandemic imagination no longer even dares to resurface without triggering fears of the (self)surveillance and (self)sanctions that the virus has made us all so familiar with since. Instead, what my Proustian petite madeleine now brings forth, is an aseptic nightmare of wires—a rather coherent Covid-free sanitized environment, liberated from people drinking, sweating, and shouting aloud together.

‘Blended learning’ is not a whiskey brand. As pompously stated by one of the thousands of learning platforms that have mushroomed out of the shadows of Covid-19, it is a ‘formal education program where students learn at least through some online delivery of content and instructions with some elements of students control over time, path, place and pace; and at least in part at a supervised brick and mortar location way from home’.

This is what we’re all supposed to do after measures such as social distancing, forced lockdown and curfews, have been implemented. The question is, within this, what are we really ‘in control’ of? What is it that makes it a ‘personalized learning experience’ and ‘unique to your students’, as the platform promotes and attempts to sell? How can we use words such as ‘individualization’, ‘personalization’, and ‘differentiation’—’tailored to meet each individual student’s needs’—to describe an experience that looks increasingly similar, as Sofie Smeets writes, to a séance?

Can you hear me?

Are you there?

If you can hear me, can you give me a sign?

Most of the platforms we use on a daily basis for work and leisure have names that suggest collectivity and togetherness. They hint toward shared spaces that do not exist, and the hinting begins from the very moment we call these spaces into being, from the moment we engage in the performance of their sociality. We say, ‘let’s meet on Zoom’ or ‘see you on Skype’, as if we are meeting on stools at a bar, on benches in public squares, or on the dance floor awaiting a concert. When in reality, we grab a drink and sip it in front of the gallery view. We watch our friends resemble the Brady Bunch opening credits, looking like a virtual stamp collection in their tidy repetitive rectangular spaces. Throughout this charade, the oddest element is that we spend the social hour not so much looking at the gathering, rather we sit there instinctively watching, monitoring ourselves.

Image via https://imgflip.com/i/4fb87q.

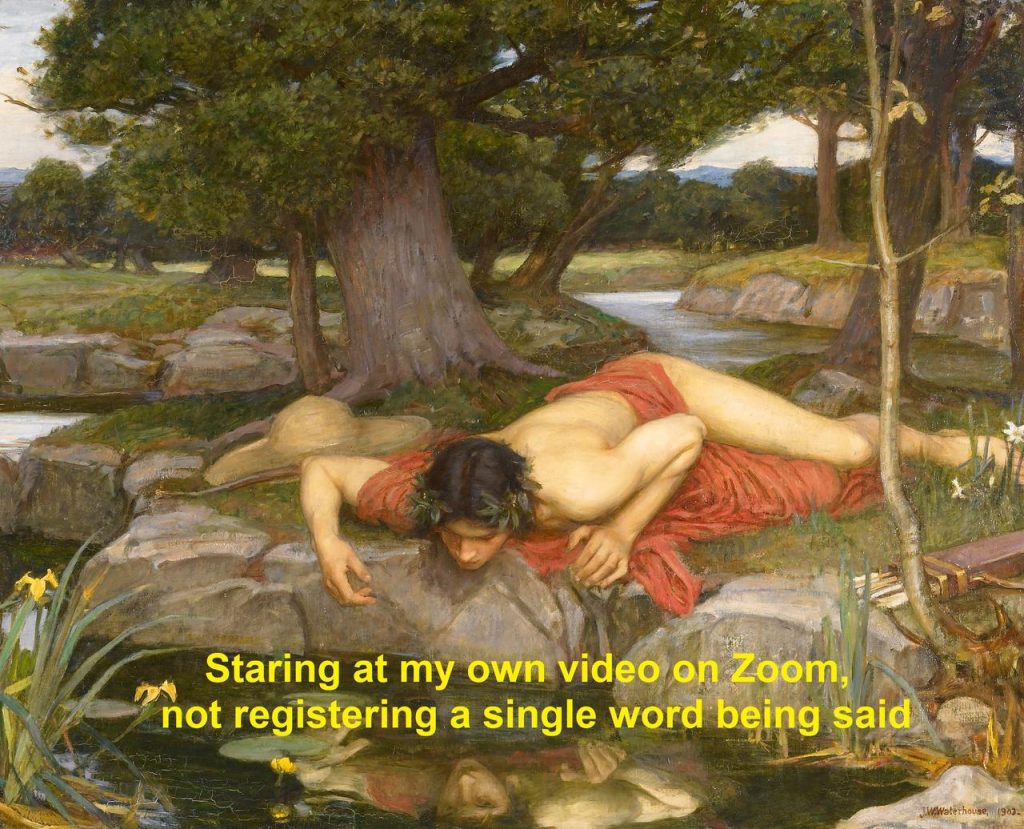

No matter whether one is casually drinking with friends, holding an online birthday celebration, showing up to a work meeting, or teaching a class—the self-reflecting gaze is always-on, ever-present whenever the camera is on too. It is a Narcissus-like situation, except instead of loving yourself to death, you develop a constant sense of inadequacy and anxiety: Do I look professional enough? Do I look good enough? Do I look fresh enough? Fix your hair, apply a ‘resting smile’, adjust the camera angle to look less puffy, less tired. Just. Look. Happier.

Tending to the Face:

From Surgery to Ring Lights, We’re all Influencers now.

The cosmetic surgery market is booming in the time of the pandemic. In the Italian newspaper Repubblica Federica, a ‘life coach’ from Bergamo confessed that once having to switch to ‘smart’ (online) working because of the lockdown, she began noticing flaws on the skin of her face, which she had not perceived to be there before. Valeriano Vinci, a surgeon from Milan, says ‘(the spike in cosmetic surgery) is a bit like what happened with selfies, now it’s because of video conference calls that we are obliged to gaze at our own image on the screen’.

How frequently do you look in the mirror? Does your face please you?

Are you disgusted to detect familial features?

Do you worship or hate your ancestors?

Do you consider your image erotic?

Do you pretend that you are a star’s child?

If you squint, does your reflection become abstract?

Is abstraction a transcendental escape from identity

or a psychotic spasm of depersonalization?

– Wayne Koestenbaum

If surgery seems a little extreme, why not try a ring light? The ring light is a face-flattering ‘doughnut of light’. A miracle lighting device that ‘cleans’ your face of all shadows by delivering brightness in a circle rather than from a single point. The ring light was a nerdy thing before March 2020. Prior to the mass-conversion to time spent in front of webcams, ring lights were part of the toolbelt of Instagram influencers, Youtubers, Tik-Tokers, and new/next generation digital ‘creators’ (the masters of online, facial performances). Pre-pandemic, ring lights were mostly known and used by those who were livestreaming from inside their home-aquariums of kitchens, bathrooms, or bedrooms, implementing their illuminating doughnuts to impress followers, gain more subscribers, and increase their likes and shares. An army of YouTubers, Twitch streamers, OnlyFans creators, Chaturbate cam models, are now sharing their hack for eternal beauty with office employees, businessmen, fitness instructors, and us—teachers.

Selfie Light Ring Advertisement, via https://www.bol.com/nl/p/selfie-ring-light-clip-pro-wit-werkt-met-aa-batterijen-voor-mooie-selfies/9200000083001604/?country=BE.

‘Americans had spent the past decade mastering the momentary muscle movements of a good selfie, but starring in a high-quality live video in front of co-workers or romantic prospects for hours at a time is a different beast entirely’, writes Amanda Mull at The Atlantic. ‘People had no idea how to contend with broadcasting their own face—weird shadows, awkward backdrops, and under-the-chin shots from low-slung laptops abounded’. How to make the flattening gallery view look alive again, as if people were moving in an actual place, crowded and swarmed with life? How to render the boring aesthetics of the rectangular into an object glowing out from the uniformity and numbness of the on-life?

Suddenly, everyone was looking for a tip to just look better, less boring, and more professional. The ring light is the revenge of Gen Z against Boomers and white-collar workers. ‘Those kids’ who spent hours dancing in front of their laptops, inventing silly choreographies, live commenting as somebody else played a video game, and making DIY tutorials for pretty much anything and everything, are now teaching the global working class a lesson. In the time of a pandemic we are all, whether we like it or not, living the backend, glamourless life of influencers. We all work for ourselves and with ourselves, from inside of our bedrooms and kitchens. Thus, the ring light has become a must-have investment, no matter your profession. It is the most wanted gadget of the work-from-home mandate.

Unlike an ergonomic chair, a specialist microphone, the latest HD webcam, noise cancelling headphones, or an oversized office printer that we had never considered to own before, the ring light is frivolous. It is a fierce reminiscence of the ‘good life’, disco culture, glamour parties, and crowded photo shoots, all bundled into one. The ring light does not originate from boring corporate settings, rather from the realms of make-up, TikTok dances, and sex cams. It glows in the dark, illuminates your visage, frees you from the visual constraints of the desk and the desktop, and most importantly, makes your skin look younger and positively radiant. Move over Bill Gates, the essential office products are now brought to you by James Charles and Charli D’Amelio. The ring light is the ultimate gift for a locked-down and curfewed Christmas. It gives all of the glamour, excitement, and frivolity one surely deserves during these dark times.

Something I would have never thought that I could have done before

is dancing in front of thousands of people

– Charli D’Amelio

The ring is said to give one ‘manga eyes’. These are the peculiar, enlarged style of eyes drawn for characters in Japanese comics. In front of a ring light, eyes become huge and perfectly round with tiny pupils and no iris. Manga eyes convey ‘a cute, delighted look’ and symbolize ‘extreme excitement’, Wikipedia says. Perfect.

How interesting […], what could it mean for history,

that a face is wrong for itself in a time in which all is also so wrong.

The animals sit forlorn or ride subways into city centers.

The water has become poison. The old behave like the young,

and the young are too worried to move.

Pilotless weapons have the names of birds, so why shouldn’t faces, also,

lead away from the facts? To the lovers of the contradictions,

these faces are a perfect account of our time: the poetry of the wrong

– Ann Boyer

With this facial upgrading-capability, and when compared to the surveillance-looking, CCTV cameras that have been installed in many educational settings, the ring light looks more like an illuminated path toward liberation. Unlike the old-school, top-down Foucaldian dispositif, which makes the student/teacher/subject feel constantly observed and under the control of a Panopticon-esque institution (continuously reminding those present that they are part of a surveillance project and performing their own role in it), the ring light juxtaposes lightness with freedom of movement. You are your own metteur-en-scene. The camera is in front of you, it glows in the dark and makes you glow return. A hovering portal that sits afore like the entry into Wonderland. There are many roles available: Humpty Dumpty, Alice, the Mad Hatter… or the Cheshire Cat?

Here, There: Any-Space-Whatever

In his essay from 1995, The Exhausted, Gilles Deleuze mentions the Cheshire Cat in a description of what he calls ‘Langue III’; a stage of language that comes after that of names and voices, of rationality and memory, of objects and representation. It’s the language of an image that is rendered into a process rather than into content, divorcing it from the thing represented, disengaging and transforming it into ‘a possible event that doesn’t even have to realize itself in the body of an object any longer’. Like the Cheshire Cat’s disembodied eyes and smile in Lewis Carroll, images appear and disappear in and out of thin air. They dissolve into space, a space, that Deleuze writes can be ‘any-space-whatever’. Here we are, from this any-space-whatever, all glowing, appearing, disappearing, and reappearing, in the shape of floating doughnut ring lights, coming to you live straight out of Wonderland.

The CCTV camera spies on us. It suffocates. The selfie-stick triggers us too hard on what we’ve lost—the travels, the freedom of movements, all of that hanging out. But the ring light stares at us with warmth. It glows before us and invites us to enter the wonder of its circle. The ring light is, in fact, our Wonderland. We are the Cheshire Cat, disembodied, disconnected from our own flesh, from the others—and from any possible representation. With big eyes, clear skin, and appeasing grin, we are still on the search for all (and any) possible connections, new algorithmic combinations to be done and undone, anything that can be liked and shared, streamed or streaked. In this never-ending set of variables and possibilities that can be tried and untried, ‘all order of preference and all organization of goals, all signification’ is lost. As Deleuze said in the title: Exhausted. Radiantly puzzled by where the tiredness is coming from.

It is here that the semantics and tactics start to bleed, blend, and become the exhausting performance. This is the real welcome into the world of ‘blended’ learning; where the same greeting is given into this hall of mirrors as it is to the mise-en-scene where ‘collectivity’ is in non-stop (re)enactment. Students and teachers alike are busy gazing at themselves, rather than at the ‘Teams’ in front of them. During a video lesson, we are not immune to the constant drive to look at one’s self. To the minute camera adjustments in search of the better angle. Worried about the personal image far more than the content you are about to deliver. In the physical classroom we might have a live performance crisis, but in the hybrid environment surely the experience of crisis is one of the gaze—not of the Other, but of the self. ‘Shall I look over here? Or over here? If you guys all look at your computer, all of you including those who are in the physical classroom, then I can look at everyone on the screen. I think this is the way to do that… how do they do it in other blended classes?’. Like Igor Vamos in his tragicomic video, all of us have uttered these words—usually in a panic. This is the crisis of the gaze: Where do I look? Here, here, or there?

Image by Adrienspawn, via https://www.deviantart.com/adrienspawn/art/Narcissus-and-Echo-845287570.

Where is it here, and where is it there? Does here suggest the physical presence, and there hint at the remoteness held by boundaryless and immaterial cyberspace? A student majoring in international affairs voices her frustration toward this imaginary line that divides the two spaces, which (unwillingly but irremediably) becomes a way to assess the ‘quality’ of students. ‘There was a general assumption by some professors that the students who were online were not paying attention, just because we were online. Things like “Oh, they are probably away having lunch right now” or, “I wonder if I have anyone’s attention from the remote students…” were said several times during my classes. Professors need to understand that being online is not like being in a classroom and answering a question in the physical classroom is much easier than doing so remotely—at least it is for me. If we do not answer, it does not mean that we are doing something else. Maybe we just simply do not feel comfortable speaking in that moment’.

Meanwhile, on the other side of the screen, teachers are required to behave like jugglers—which is not the easiest thing to do whilst also experiencing performance anxiety. Antonio Lopez, a teacher of communication and media studies, explains; ‘When the majority of students were physically present, it seemed to be smoother because most of my attention could be in the classroom and I could incorporate the online students easier. The dynamic reversed itself once the majority of students were online and only a few were in the physical classroom. At that point it just felt like a farce’.

Behind the curtain, in the pantomime

Hold the line

Does anybody want to take it anymore?

– Queen, The Show Must Go On

The Tyranny of the Rectangle

With professors and students both lost, the interfaces we use simply do not help us overcome the geographical confusion to find our bearings. The gallery view reduces the environment to a sequence of geometrical forms and quantified tiny spaces, putting each student into a little cage, forcing the entire education experience into the aesthetics of the rectangle. This is what a ‘team’ looks like in the age of the pandemic: a grid of isolated box shapes confined to unbreakable bounds. You cannot cross the borders of your rectangle, just as you cannot go out of your apartment. Spaces are limited and delimited, even in the limitless domain of the digital. ‘It’s very difficult to create a space of connection, a space of togetherness within this aesthetics of the rectangular’, a communications senior student expresses.

The rectangular is what drives attention towards yourself rather than diverting it to others. There is no real Meet happening in Teams. In the solitudinal aesthetics of the rectangular, the only thing to Zoom in on, is yourself. Going beyond yourself means engaging with floating icons that most likely only carry initials (camera off), as if they were patients under medical observation whose identities need to be kept anonymous.

Tyranny of the rectangle. Image via https://medium.com/jacob-morgan/the-office-space-isn-t-dead-it-s-making-a-comeback-b13d5ac206f0.

The once innocent, banal rectangular has turned into a powerful self-containment device and peer surveillance tool. ‘When online, there’s no one to hide behind when all the squares are lined up next to each other, and I’m much more aware of how clean my apartment is in the picture behind me’, says Madison, a grad student in art history, ‘I’m guilty of spending a lot of time looking at my own square when the camera is on. I’m constantly checking to make sure I’m still in the frame and that I’m not making any faces/reactions that I wouldn’t make in class’. ‘It is weird’, adds Briana, a student in communications, ‘[…] when physically in class I am completely able to focus my attention on both watching and hearing; online, I was not able to do these two things at once. I was distracted by looking at other people’s faces, or my own’.

A truth is that in physical presence we are never confronted with our own gaze, neither as teachers nor students. We do not get to see the resting grimace on our face, or our eyes blinking as we explain a concept, just as students do not have the chance to check whether they have a clueless stare or a glimmer of curiosity toward what is being said. Blended learning has put us in the awkward situation where we have to not only sit in constant confrontation with our face, but find the best way to check (and adjust) our expressions to make them convey a certain deliberate emotion, from interest and curiosity, to visible passion and participation.

_The impassive face has its rival: the face that can never hold still.

The face is kinetic, elastic,[…] the curse of digital photographers

and bio-informationists who must try to fix,

in data, what is in its very form unfixable.

This face provides an onrush of information which comes so quickly it almost evades processing:

this face is prolific, a human comedy of feeling […]_

– Ann Boyer

Moving from the hypertrophic self-reflecting gaze of the ‘selfie’, which was widely interpreted as a mere sign of the empty aesthetics of pure narcissism, video-calling platforms have added an unprecedented (self)disciplinary dimension. The environment constantly reminds you of your presence and of the Others’. Ironically, it is precisely when acquiring a disembodied status that we are reminded of our flesh and bones, skin and muscles—by this enduring and endless mirror gaze.

‘If the camera is on, I often look at myself, making sure I am ‘presentable’ (something I would not care about during a live in-person lecture, as I would not be able to see myself)’, tells Giulia Villanucci, who is enrolled in a master program in the United Kingdom. For Briana, the sense is more a matter of ‘being watched’; ‘Although I knew it was not the case, it made me stressed’. Matjia, a communications senior who has been remote from Serbia for the entire semester, echoes the same concerns, adding that ‘It seems as if all eyes are on you constantly and you’re being surveilled. This, of course, is both good and bad at the same time’.

‘…I enter light and it’s from the gaze that… I am photo-graphed’. The camera appears to have finally acquired the magical power of ‘looking at you’. In the anecdote of the sardine can that Lacan recalls in Seminar XI, a young Lacan is out at sea on a boat with a group of fishermen when one of them, who goes by the name of Little John, points to something floating in the water: ‘You see that can? Do you see it?’, Little John says to young Lacan, who becomes anxious in a state of discomfort, ‘Well, it doesn’t see you!’. Sorry Little John, but in fact, it does see you. It does see us now the object gazes back. The mere fact of the built-in webcam reminds us that we are constantly gazed upon, being watched, and under surveillance. ‘In the depths of my eye the picture is painted, but the subject is not in the picture…if I am anything in the picture, it is always in the form of the screen…the stain, the spot,’ later wrote older Lacan.

Camera On, or Camera Off:

That is the Question

If hypervisibility implies hyper (self and peer) surveillance, then how do you call presence into being in the absence of bodies, in the lack of a physical shared space and its light, smell, and shape? Camera-on has come to mean ‘presence’ in the blended learning environment. ‘Why don’t you guys switch your camera on, at least at the beginning of class, so I can see you, you can see each other’ is the ubiquitous plea of teachers. A begging and desperate attempt from their side to not teach into the void in preference for staring at other people’s faces alongside their own—even if the other faces are reluctant and disinterested. By now this request is frequently met with ‘Sorry professor, I have a bad connection’, or ‘Unfortunately my camera does not work’, or ‘I am connecting from my mobile, I don’t have enough bandwidth to turn my camera on atm’, to which the teacher is obliged to answer: ‘Sure, no problem’.

Lately, there are increasing suggestions to enforce the use of cameras as a proof of attendance, in the hope that it will encourage students’ participation. ‘Sleeping with camera on: classic! I much prefer it to the mute rectangle’, a professor in public speaking tells me, who is strongly in favor of having all cameras on during class time. Giulia Martinez Brenner, who studies in the Netherlands, writes: ‘I cringe when the teacher asks the class those questions. The ones that aren’t even proper questions, just ones to check and see if everyone is there and following. I stare at the sea of initials and think about my own, GM, that are currently hiding our pitiful conditions. I’m slumped over my chair, obviously still in my pajamas, resembling some sort of slimy invertebrate more than anything else. I have Instagram open in one hand, a coffee in the other, and I can’t help but give a small smirk. I can get away with this? Without doubt it’s a childish satisfaction. I try to convince myself it’s freedom… but is it? The initials stay silent. The professor asks again, and my anonymity hits me with a surge of guilt.’

Carlos, a student in international business, is firmly convinced that ‘Cameras should always be on. It is a sign of disrespect to the teachers and fellow students if the camera is off while they are speaking or interacting and I believe “awkward” is not enough of a word to express how it feels’. Briana also empathizes with the professors, noticing that ‘it was a bit sad when they would gaze at our initials because no one had their camera on, since they probably felt they were talking to nobody’. And yet she adds: ‘This, though, was controversial for me because, while I did want to keep the professors company, I knew I was going to be less engaged if I turned my camera on.’

Meme via https://memes.com/blog/these-hilarious-zoom-memes-are-way-to-real.

The shadow of anonymity covers up something other (or more) than lack of interest. If one is embarrassed by their physical presence, they might very well opt for not turning the camera on. A teacher in my communication department tells me that he was enforcing the use of the camera. He eventually gave up on this practice, realizing—only after a long email exchange—that one of his students who had never shown up on camera had a problem with their body image, feeling overweight, and hated their reflection so much that they did not even allow mirrors inside their apartment.

Besides the reflection of the self, many students, as well as teachers, do not have the luxury of living in beautiful, spacious apartments. There is a huge variety of housing situations—from living in a foster home, to having only a bed in a shared space with many others, or even being a grown-up still living at home with Mom and Dad—this is where ‘camera off’ hints at embarrassment rather than laziness or lack of commitment. ‘Camera on’ has turned into a luxury option that under-privileged people, migrants, proletarians, or anyone experiencing a physical or mental disorder (including stress and anxiety), simply cannot afford. Rather than helping class participation or facilitating the learning experience, it has become an exclusive, divisive, and ultimately oppressive, tool.

Before being tool to surveillance and discipline, the camera is a technology of the self. The camera carries the quasi-magical power of individuation, the quality of putting the self into being. ‘My camera is off. I started turning it off because I hated catching glimpses of my face in the corner, and I hated even more the thought that other people were seeing the same thing’, Giulia Martinez-Brenner writes. If we opt toward merely sanctioning the option of camera-off, without understanding why some prefer it in the first place, we risk losing track of this powerful aspect of the construction of the self.

From a student’s perspective, the ‘always on’ camera might generate the endless anxiety of having to restlessly perform the self and put it into being in front of others. This anxiety is, however, not only a ‘student thing’. During this busy semester of ‘webinars’ all over the place, I heard more than once the solemn declaration being spoken by organizers: ‘It’s nice for our speakers if they can see/hear other people in the panel, it’s not just our students who are shy…’. ‘It would be nice if folks can turn their cameras on or unmute themselves, so panelists can feel the energy of the crowd… can feel that they are, in fact, speaking to an actual crowd’. And so on.

YouTube videos and practice have taught me all I know

– James Charles

Theatres and cinemas may be shut down, but never has there been so much space for performance of the self. In endless Zoom-Teams-Meets we are confronted on a daily basis with the absence not only of the body, but also of faces and voices, performing for the self rather than for others, continuing to maintain the veneer that things are ‘kind of’ normal and business goes on ‘as usual’—that all of this has simply moved to a different space, and only temporarily (or so, we kid ourselves). We take to this performance both for ourselves, and on behalf of a system. For an infrastructure of life that we desperately want to keep intact while we are well aware of its collapse. Here it lies, what we already know: Our daily performance is nothing but a farce.

Intimacy Out of the Dark

And yet, sometimes, in these disembodied communications launched into the void, something ‘intimate’ might come to emerge from the darkness. A communications senior reports on a teacher who plays soft music in the background while talking over the slides and sharing the screen: ‘This voice over with the light music in the background creates a certain intimacy, a shared space, a space for connection’. Another teacher uses the same word, intimacy, to describe the space created by the faceless sounds he encounters daily in his blended teaching. He is also convinced that sound might be a more powerful dimension—and far more suitable to our internet bandwidth—than video sharing. It appears that the sound dimension can be a liberation from the self-centered (and hyper performative) gaze, providing a way out of the aesthetics of the rectangular.

I cannot help but be reminded of ‘songs playing from another room’, a YouTube microgenre initially made up of pop songs from the 80s and 90s that have been remixed so as to sound as if they were, in fact, being played from another room. This genre now includes hundreds of thousands of remixes from contemporary artists, ranging from Tame Impala to Lana del Rey, and beyond. Jack Wilson, an expert in YouTube videos featuring ‘songs playing from another room’, writes that ‘while these videos are vectors for a number of affects—nostalgia, recalling memories (real and imagined), mourning—and while these affects are diverse, the point from which they emerge is the same: a synthetic sense of something occurring that we are not a part of’.

This ‘something’ we are not part of (or no longer part of, at least for the time being) is the overcrowded room. The one too hot in summer, and too stuffy still in winter. The one with too much noise coming from the street below. This is the same one with the blackboard that’s always scribbled upon from previous classes, the one with a desktop computer that’s barely working. The disembodied sound dimension, and its potential for a freeing-up from the anxiety of the hyperconscious self-gaze, might help create an opening for spaces of intimacy and in defiance of connectivity—with its low-fi, low-tech, glitchy sound, indifferent to the glossiness and emptiness of the high-res camera. Connectivity does not always equal connection—and vice versa.

Teacher, Call Center Operator, Food Courier:

One and the Same?

A colleague tells me that he thinks about teachers as similar to call center operators. Weird hybrid bodies, somewhere in between the exploited workers of the contemporary service industry and the vintage romantic image of switchboard operators from the 1950s. On the one hand, they are helping people connect and get in touch; on the other hand, they are playing into the myth of efficiency and multitasking—headphones on, responding to queries no matter the time, place, or condition, they’re coming from. We are service operators in isolated cells. No doubt feeling alienated ourselves, how is the operator-come-teacher able to create empathy with others while experiencing the same lonely seclusion.

Teaching ‘on demand’ alludes to educators as not-so-different to food couriers. Customers(/students) open their apps at any time, selecting their goods, ordering and paying, to a 24/7 temporality. Then, someone will deliver it wherever is needed, day or night. Eventually, a consumer will fill their bellies, which in turn should make the courier happy, as they have fulfilled their ‘mission’. In March 2020, during the most severe phase of the Italian lockdown, one of the few working categories allowed to move freely around the city were the heroic bike riders, the food couriers. Just like them, we teachers fight the starvation of souls and provide emergency care, delivering ‘food for thought’, one could say.

Are we stuck into this suffocating binary, somewhere between being quick-response call center operators and valorous food couriers? Are we entrapped in the multitasking, efficiency, on-demand, game? Are we condemned to be switchers and bikers without having our own switchboard, our own bike?

Many among students and teachers think that asynchronous is a better solution for the challenges of our times. Record a class whenever and wherever you want, upload it, leave the students consume it at whatever time suits them, which eventually ends up lowering the participation rate even further. Briana speculates that ‘the fact that classes were recorded was perhaps an additional reason to why people did not ask questions or comment on the material. They were uncomfortable knowing that their comments could be heard over and over or could stay forever on the chat’.

In Praise of Awkwardness

Can you hear me?

Are you there?

If you can hear me, can you give me a sign?

Recalling the séance situation of the online classroom: ‘A séance is an attempt to communicate with spirits’. We sit in the blended session attempting to call forth the presence of the Others, simultaneously trying to make our own presence present, while remaining in the absence of both. Séance is a freakily fitting word for the palaver; coming from the French word for ‘session’, and from the Old French seoir, ‘to sit’.

These séance-calls of endless fine-tuning procedures take forever. This is to the utmost annoyance of everyone involved, both teachers and students. ‘Blended learning’ mostly sounds like ‘Can you guys hear me?… You need to unmute yourself. Can you see my PowerPoint?’ ‘This is how any and every student presentation started this semester’, a senior student in art history tells me. Antonio Lopez also shares this frustration: ‘It’s very difficult to maintain a natural flow of weaving discussion and lecture while at the same time having to manage all the technology. Under normal circumstances, I just launch Youtube videos from the class Moodle page and we watch and discuss them together in class. But I could not stream the videos to online students, so they had to watch them on their own using the Moodle links. It was a hope and a prayer that when I showed the video in class, the students at home were also watching it on their own and that our timing synched up’.

Madison also reflects on the amount of time spent on making the tech work. ‘On days that were truly “hybrid” (in that some of us were in class and others at home), we almost always had to start class late because of technical issues. From the perspective of a student in the classroom, it felt like the distanced students didn’t have to engage as much. From a distanced-student perspective, it felt like it was harder to gauge the classroom (e.g. I couldn’t tell if someone in the class was trying to speak since the camera faces the board), so I didn’t feel as comfortable participating as I normally would’.

The discrepancy between the promise of seamless real-time delivery, efficiency, and speed that comes embedded with assumptions of the digital, and the much more messed up and messy reality made of glitches, interrupted sound bites, frozen frames, and abrupt disconnections, creates what anthropologist Rebecca Stein calls lapse: ‘An analytics of lapse writes against theories of technological progressivism and dreams of techno-modernity by spotlighting sites and examples where technology fails, somehow, to deliver on its promise’. While the concept originated in the context of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, it gives insight for reflecting upon what is happening in our classrooms, kitchens, living rooms, and lives.

Lapse is the hiatus, the gap, the abyss that separates the bright, utopian dream of techno-solutionism and the cruel reality of techno-dysfunction. The lapse is that awkward moment when the teacher has prepared the perfect PowerPoint, adjusted the camera and the light to catch the best angle of the face (wrinkles and frowns carefully expunged from the frame), found a brand-new background that makes one look like they’re speaking from the outer space (deleting the reality of the tiny, chaotic, sad studio)—and then, all at once, everything goes awry. The bandwidth doesn’t fulfil its expected presence and performance. We all know this moment: Suddenly you’re unable to display the PowerPoint and your face simultaneously (It worked earlier today, I swear!) and have to make a real-time decision amid the flurry of embarrassment.

And so, you give up on everything. From the special background to that perfect camera angle. One ends up doing a solo performance to the screen; forsaking your face for the bright PowerPoint, now simply speaking into the void.

Regardless of the amateur antics that arise, Madison writes: ‘I think that overall I prefer in person learning, but the “hybrid-learning” experience made the best out of the situation at hand’. I, too, feel that no one would disagree. We were forced into this blended, hybrid (call it what you will) environment because of an emergency. And surely, we are lucky to have what we have—lapses, glitches, frozen frames, floating icons of initials, un-called for cats wandering across screens, and all. These flaws and irritations are better for making do with than nothing.

Recently, a video work I made with one of my former students was part of an (online) exhibition called ‘no-longer-being-able-to-be-able’. Hang Li, the brilliant young curator, took inspiration from Byung-Chul Han’s The Burnout Society. Hang Li writes that the exhibition ‘questions the contemporary life immanent in excessive positivity and information. In such a society, feelings of exhaustion, anxiety, and disorientation, are growing within obese bodies that are indoctrinated with neoliberal fantasies. The pandemic, which could be a pulse of the myth of endless positivity, expansion, competition, and exploitation, has seemingly turned out to be revealing and reinforcing the “normal” way of being (in both the art field and societies-at-large). In response to the neoliberal norm of being-able-to-be-able, no-longer-being-able-to-be-able attempts to unpack the culture of excessive positivity, ceaseless expansion, and overaccumulation. It also attempts to discuss the potential ways of expression and resistance amid the overloaded, oversaturated, and overdrawn existence’.

During the first (Zoom) meeting to get to know the other artists involved and exchange views, Hang Li timidly apologized: ‘I wanted to play the sound of the video I am showing, but I am not being able to, because my partner is working in the same room.’ Suddenly, the meeting turned into lots of people apologizing as they wanted to switch the camera on but were ‘not being able to’ as they didn’t have enough bandwidth or had other people in the room that were also trying to get stuff done.

Decontextualising Zoom. Image by Alex Kim via https://www.are.na/alex-kim-xtt9rcpqpvs/decontextualising-zoom.

This ‘not being able to’ was precisely the point. We could have declared that we were doing our best to cope with the situation and produce art, learn, and teach. That was not always possible though, as expectations only sometimes met wishes and desires. We collectively found that ‘blended learning’ and other bombastic names, myths of efficiency and hyper-connectedness, hypertrophic self-oriented gazes and high-res surveillance cameras, were the rubbles of the neoliberal moment lying behind us. It was within this that we (silently, and together) came to decide that it was just fine being, and feeling, awkward.

Many students told me that emojis sent in chats during online sessions might not make the teaching and learning process more efficient, but they do make it more fun and less tense. Antonio Lopez described how ‘for the last day of class one student used a background image of a nuclear explosion, which made the whole class laugh’. With GIFs, hearts, smileys, and even raised hands—all of which are useless from a teacher’s perspective as you are not able to monitor the chat while you’re trying to juggle between camera, PowerPoint, connection problems, etc.—elements can be utilized that are ‘merely’ something fun and that help release the tension of overly intimidating and frozen atmospheres. In the absence of a body, an emoji can help do the job. When internet connection fades in and out, a simple round of chuckles might make up for the fiber’s failures.

Acknowledging the awkwardness of the situation, whether it being face-to-face, hybrid, or entirely online, can be of great solace. The aesthetics of contemporary online platforms tend to optimize sound and video in order to render a seamless experience of presence. However, human awkwardness irremediably makes its way back in the video call, within all the glitches and frozen frames, within interrupted sounds and unasked-for echoes. Geraldine Snell, an artist who is part of the no-longer-being-able-to-be-able exhibition says ‘We should let go of the shame… We shouldn’t be ashamed of our real-life background, of the noises at our place, of the people we live with’. Recounting a Zoom experience she had with some BFA students, Anna Frijstein, another artist from the group, emphasizes how they had explored collective care through vulnerability and shame. ‘It was “awkwardness” that was the overarching feeling for both the participating students, and definitely for myself as the performing teacher. Feeling vulnerable, exposed and awkward because of the virtual “voidness”’.

If any lesson should be learned from the past ‘blended’ year, it would be to welcome—and celebrate—awkwardness. As Franco Berardi writes in Futurability: The Age of Impotence and the Horizon of Possibility, competition and its predatory rules have resulted in reducing our ‘ability to feel compassion and to act empathically. The hyper-stimulated body is simultaneously alone and hyper-connected, subject to psychological and emotional exhaustion’. We are inculcated with the myth of performativity and efficiency, when instead we get loneliness and depression.

Rather than perpetuating the farce of performing the self, we could get acquainted with the awkwardness inherent in this very farce. Instead of ignoring that ‘awkward moment’, why not celebrate it? ‘That awkward moment when someone farts in the car…’, ‘That awkward moment when you have already said “what?” three times and still have no idea what the person said, so you just agree…’, ‘That awkward moment after you’ve already taken a bite and someone starts praying for the meal…’, ‘That awkward moment when you wave to someone, but they don’t wave back…’ The internet is full of awkwardness, of which it seems only meme culture is in constant celebration of.

Meme via https://brandedbridgeline.com/blog/conferencecalling/conference-call-humor/.

Poet Wayne Koestenbaum writes in his book Humiliation: ‘Performers spawn performers, an intergenerational saga of distress. Liza (in the eyes of a shame-hungry public) is humiliated by inability to reach her mother’s pinnacle, or by inability to reach her own former pinnacle. Past triumphs rise up to humiliate the present self’. Humiliation is a tribute to that ‘abasement of pride’—as Wikipedia defines the feeling— ‘which creates mortification or leads to a state of being humbled or reduced to lowliness or submission. It can be brought about through intimidation, physical or mental mistreatment or trickery, or by embarrassment if a person is revealed to have committed a socially unacceptable act’.

Right there, on the avenue of embarrassment, is where humiliation meets awkwardness. It thrives upon the clumsiness of your well-rehearsed professional performance that stumbles on impact with bad bandwidth, slow connection, frozen frames, a kid screaming in the background, the family dog’s impromptu barking, and the cat purring right in front of the screen—not to mention the merciless close-up of a pimple growing bigger and bigger from the stress and anxiety of it all. Why don’t we take the shame element out the picture (so to speak), and embrace the awkwardness as a vaccine against hyper-performativity and self-burnout? To paraphrase Koestenbaum: Imagine a society where awkwardness is essential, ‘as a rite of passage, as a passport to decency and civilization, as a necessary shedding of hubris’. Why not make a space for potential flourishing out from our own self-acknowledged impotence and collective discomfort? How about we just make the best, make maximum awkwardness, make shameless fun, of this one massive ‘awkward moment’ that we’re living in?

I want to thank Student Government and all the students and professors at John Cabot University in Rome who have given me insights and feedback on their ‘blended learning’ experience. Thank you also to Giulia Villanucci, Giulia Martinez-Brenner, Hang Li, Anna Frijstein, Geraldine Snell, Lyric Dela Cruz. At INC I want to thank Geert Lovink for his support, Jess Henderson for the copy editing and Marijn Bril for the design.

Donatella Della Ratta is a scholar, writer, performer, and curator specializing in digital media and networked technologies, with a focus on the Arab world. She is Associate Professor of Media and Communications at John Cabot University, Rome.

twitter: @donatelladr

REFERENCE LIST

Franco Berardi, Futurability: The Age of Impotence and the Horizon of Possibility, Brooklyn: Verso Books, 2017.

Ann Boyer, ‘Erotology III: Categories of Desire for Faces’, A Handbook of Disappointed Fate, Berkeley: Small Press Distribution, 2018.

Gilles Deleuze and Anthony Uhlmann, ‘The Exhausted.’ SubStance 24.3 (1995): 3–28.

Byung-Chul Han, The Burnout Society, Redwood City: Stanford University Press, 2015.

Wayne Koestenbaum, Humiliation, London: Picador, 2011.

Jacques Lacan, The Seminar Book XI: The Four Fundamental Concepts of Psychoanalysis. Ed. Jacques-Alain Miller, trans. Alan Sheridan. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1998.

Rebecca L. Stein, ‘Go Pro Occupation: Networked Cameras, Israeli Military Rule, and the Digital Promise.’ Current Anthropology 58.S15 (2017): 56-64

Jack Wilson, ‘(playing from another room).’ in: Video Vortex Reader III Inside the Youtube Decade. Ed. Geert Lovink and Andreas Treske. Amsterdam: Institute of Network Cultures, 2020.

This article was originally published on The Institute of Network Cultures blog.

Articolo precedente Prossimo articolo

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License ove non altrimenti specificato